Your Weekend History Lesson From The Master

Another Fuck Around And Find Out Moment After Three Weeks

(Editor’s note: Charles Pierce writes daily at The Esquire Politics Blog at Esquire.com. He is an award-winning writer and author, most recently Idiot America. Every weekend, he sends out a weekly newsletter to subscribers, of which, I am one. Here is this week’s musings)

February 8, 2025

On Thursday, after a noble but failed attempt by the Democrats in the Senate to throw sand in the gears, the Senate confirmed a man named Russell Vought to be the director of the Office of Management and Budget, a banal-sounding agency of considerable power. Vought is a principal author of Project 2025, the Heritage Foundation's blueprint for a radical restructuring of almost every facet of the federal government and a plan for an imperial presidency far beyond the expected limits of that now hackneyed phrase.

Vought is a true believer in some pretty gamy stuff. Vought, is the founder and former president of the Center for Renewing America, one of the multifarious intellectual chop-shops funded by the bottomless reservoirs of wingnut welfare. He is an out and open Christian Nationalist, as is his organization. And that Christian Nationalism is the mainspring of an authoritarian agenda. From Politico:

Christian nationalists in America believe that the country was founded as a Christian nation and that Christian values should be prioritized throughout government and public life. As the country has become less religious and more diverse, Vought has embraced the idea that Christians are under assault and has spoken of policies he might pursue in response.

One document drafted by CRA staff and fellows includes a list of top priorities for CRA in a second Trump term. “Christian nationalism” is one of the bullet points. Others include invoking the Insurrection Act on Day One to quash protests and refusing to spend authorized congressional funds on unwanted projects, a practice banned by lawmakers in the Nixon era.

The president tap-danced away from Vought and Project 2025 throughout the last campaign, claiming at one point that he didn’t know what it was, a barefaced non-fact if there ever was one. He is its perfect product. His view of executive power is reckless and vengeful, two traits to which the American presidency has been uniquely vulnerable ever since it was first devised. All it took was a president willing to make those traits into his administration’s raison d’etre and a network of underlings willing to make those traits their own. Enter Russell Vought and the rest of the root weevils currently undermining all the federal agencies.

All the way back to The Federalist Papers, scholars from across the ideological spectrum have warned about the potential for presidential abuse. In 2008, Gene Healy of the libertarian Cato Institute called out what he called as “Situational Constitutionalism” in his book, The Cult of the Presidency:

By the mid-1970’s, motivated partly by the “emerging Republican majority” in the electoral college, the Right had largely abandoned its distaste for presidential activism and had begun to look upon executive power as a key weapon in the battle against creeping liberalism. Sadly, that pattern is all too common in political battles over the scope of presidential power.

The difference between the fundamental debate over the power of the presidency and our current political moment was that most of the other episodes in our history took place within commonly held constitutional limits. The fights were over the extent of presidential powers under the Constitution. In the current administration’s rampage through the Executive branch, the Constitution is less than an afterthought.

For example, an important part of Vought’s scheme to increase the power of the presidency is his belief that the president has the power to impound money already appropriated by Congress. This is a trick Richard Nixon tried to pull in 1974, but the Supreme Court slapped him down in Train v. City of New York while Congress passed the Impoundment Act which established Congress’ right to rule on any attempts by the Executive to impound previously appropriated money. Vought’s views on impoundment guarantee a constitutional brawl that will reach the Supreme Court, and god alone knows how that will go, the Court having already enabled this administration by its rulings on presidential immunity and eliminating the “Chevron doctrine” in the evaluation of congressionally mandated programs and policies.

This was not the political context in which previous assertions of executive power were adjudicated within recognized constitutional limits. (We exempt for the moment those debates which were conducted during wartime or during existential political crises like the Great Depression.) This was true even when the issue was over money, which is the fundamental motive behind any American political debate.

If all of this sounds very familiar, it should. The current president looks upon Jackson as a role model.

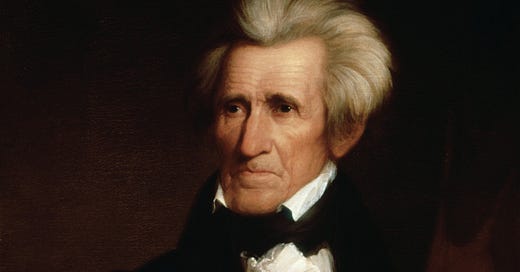

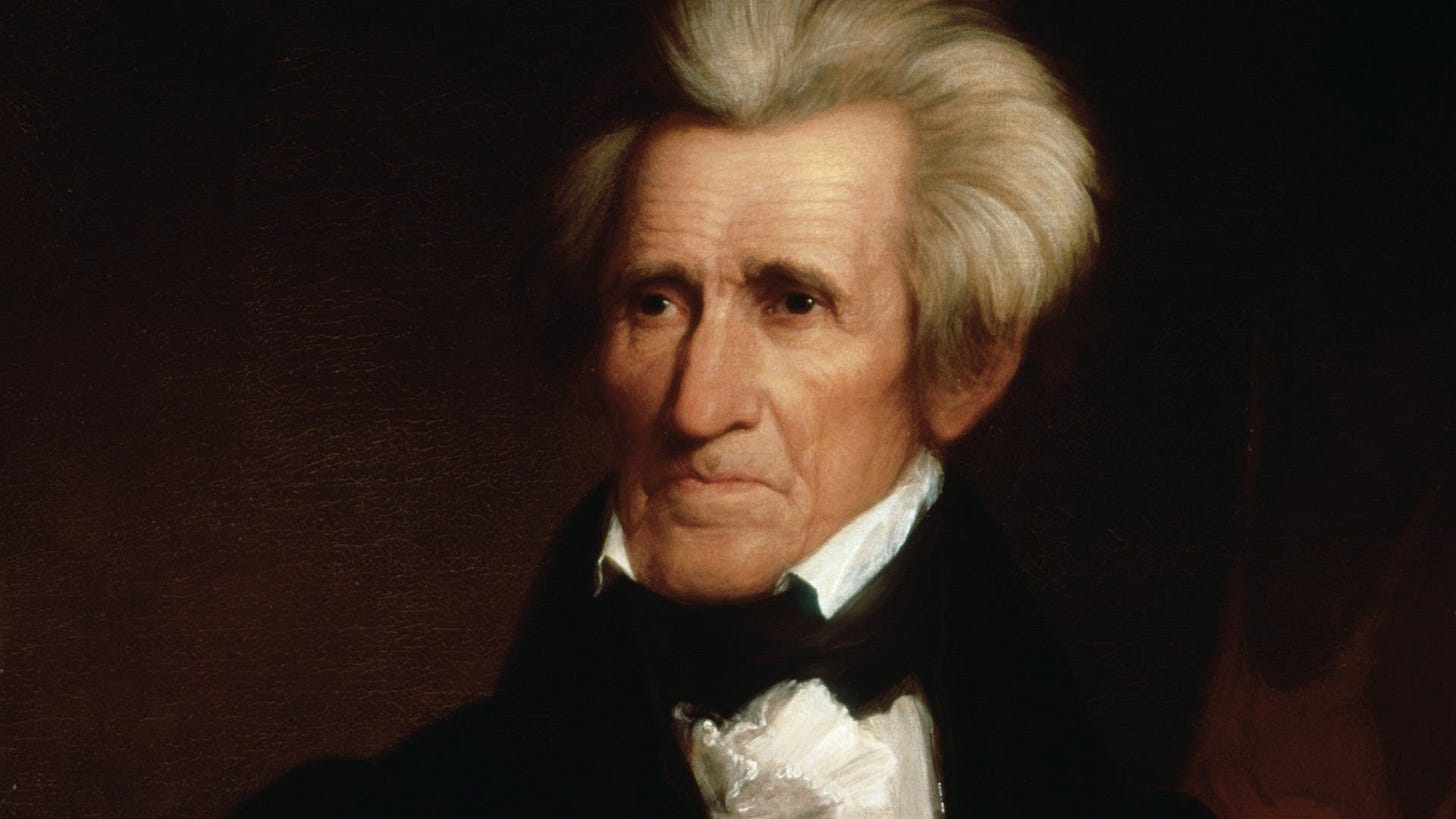

In 1832, President Andrew Jackson went to war with Congress over the Second Bank of the United States. His innate distrust of centralized economic power, the beginnings of American populism, led him to veto a bill that would renew the bank’s charter. This set up a confrontation with the Congress that, if you squinted hard enough from its height, you could even see the Civil War coming. The First Bank of the United States also had been born in controversy; it split the administration of George Washington, The Second Bank of the United States, chartered in the wake of the War of 1812, had overcome some early chicanery by its operators to become a solid institution. But its adherents had not reckoned with Andy Jackson.

Jackson came to the presidency with a deep sense of grievance against his enemies, real and imagined, in the existing political establishment and with a conviction that the government had fallen from Jeffersonian austerity into profligacy and corruption. This he was determined to reverse. The Bank was barely mentioned in Jackson's 1828 successful campaign against incumbent John Quincy Adams. But, after assuming office, Jackson learned of branch officers using the Bank as what one Jackson partisan called “an engine of political oppression” against his followers. Asked to explain, Bank president Biddle pronounced the charges “entirely groundless.” He affirmed the Bank's forbearance from politics-and its complete independence from executive control…

…The Bank's constitutionality and expediency were “well questioned,” said Jackson, “and it must be admitted by all that it has failed in the great end of establishing a uniform and sound currency.” It was a statement at variance with facts. The Bank's notes, unlike those of many state-chartered banks, circulated everywhere at face value, their integrity unquestioned. They were as good as gold.

If all of this sounds very familiar, it should. The current president looks upon Jackson as a role model.

And in a devastating irony, one of the primary architects of Jackson’s strategy was James Alexander Hamilton, the son of the earlier aerated Founding Father. The younger Hamilton concocted the theory that a national bank was facially unconstitutional, something that must have set Daddy spinning. In his veto message, Jackson denounced the bank as a vehicle for a privileged elite.

In the full enjoyment of the gifts of Heaven and the fruits of superior industry, economy, and virtue, every man is equally entitled to protection by law; but when the laws undertake to add to these a natural and just advantages artificial distinctions, to grant titles, gratuities, and exclusive privileges, to make the rich richer and the potent more powerful, the humble members of society-the farmers, mechanics, and laborers-who have neither the time nor the means of securing like favors to themselves, have a right to complain of the injustice of their Government.

One of Jackson’s primary opponents in Congress was Daniel Webster, then a senator from Massachusetts. In a response to Jackson's veto, Webster framed the issue as being over separation of powers and the limits of the presidency.

But if the president thinks lightly of the authority of Congress in construing the Constitution, he thinks still more lightly of the authority of the Supreme Court. He asserts a right of individual judgment on constitutional questions, which is totally inconsistent with any proper administration of the government or any regular execution of the laws. Social disorder, entire uncertainty in regard to individual rights and individual duties, the cessation of legal authority, confusion, the dissolution of free government—all these are the inevitable consequences of the principles adopted by the message, whenever they shall be carried to their full extent. Hitherto it has been thought that the final decision of constitutional questions belonged to the supreme judicial tribunal. The very nature of free government, it has been supposed, enjoins this; and our Constitution, moreover, has been understood so to provide, clearly and expressly. It is true, that each branch of the legislature has an undoubted right, in the exercise of its functions, to consider the constitutionality of a law proposed to be passed. This is naturally a part of its duty; and neither branch can be compelled to pass any law, or do any other act, which it deems to be beyond the reach of its constitutional power.

Jackson eventually won the issue. The Bank of the US was not rechartered, and Congress reacted by dropping the first censure of a president on him. Which didn’t matter because he had his allies rescind it later. And the question went rolling on through the rest of American political history, contained within agreed-upon limits, until this year, when it became unclear what those limits really were.

History has been doing too much rhyming in the past three decades since January 20.